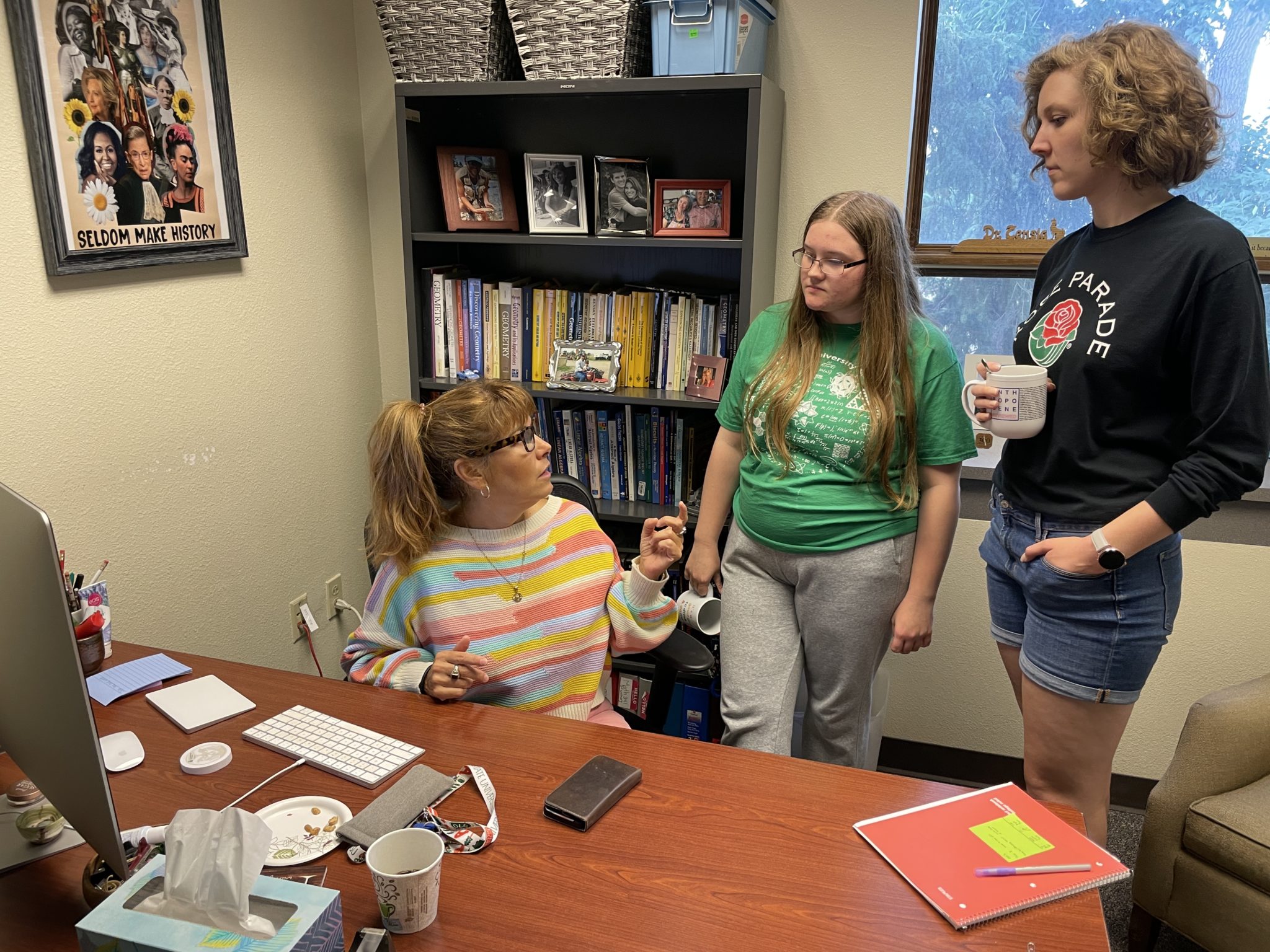

Hortensia Soto, a professor of mathematics at Colorado State University and the first Mexican president-elect of the Mathematical Association of America, has a passion for mathematics education and for helping people.

Hortensia Soto, a professor of mathematics at Colorado State University and the first Mexican president-elect of the Mathematical Association of America, has a passion for mathematics education and for helping people.

“Tensia seems to find time to do it all and has worked with other researchers across the U.S.,” said Liz Arnold, an assistant professor in the Department of Mathematics who started at CSU at the same time as Soto. “She’s actively publishing in top-tier mathematics education research journals, she mentors scholars as they work on establishing their research programs, she’s been involved in NSF grants as a PI, she provides consultation services to mathematics education research projects, she facilitates professional development opportunities for teachers, from kindergarten to college-level, and she facilitates outreach programs for K-12 students.”

After admiring Soto’s long list of accolades, it might not be immediately apparent that her parents only have a third-grade education.

“This is not a ‘woe-is-me’ story,” Soto explained. “This is a ‘yay me’ story. I work at a great institution, I work with great students, I have wonderful colleagues. My career has prospered and I’m grateful for that.”

Soto is well known in the world of mathematics for her research on embodied cognition, her compassion for each student as an individual, her work ethic and her desire to normalize failure on the path to success.

Early life

Soto was born in Belén del Refujio, Jalisco, Mexico and raised on a farm in western Nebraska. She spent the summers working out in the fields, and although “it wasn’t the best life,” she said, “I learned to work, to be grateful and to love school.”

Soto credits much of her success over her career to her parents, her generous community in Nebraska and an incredible lineup of teachers who consistently committed to her academic growth. Her parents’ work ethic and mentorship uniquely prepared Soto for a prestigious career.

“I didn’t speak any English until I started school. What I can tell you for sure is that I had the best teachers. I’m very grateful for that.”

Soto’s initial spark for math began in ninth grade, when she had a teacher who brought mathematics off the chalk board by instructionally scaffolding activities, a process where a teacher breaks up learning into structured segments to enhance learning. She fell in love with the organization of math, the problem solving and the chance to make each problem beautiful and easy to follow.

In such a small school district with few resources, Soto even began to serve as the substitute mathematics teacher when necessary.

Moving on from failure

Soto first attended Eastern Wyoming College and then completed her bachelor’s and first master’s at Chadron State College in Nebraska. She taught her first college-level math course 34 years ago.

“I was hooked,” she said of teaching in higher education. “It just felt right.”

When she moved on to get a second master’s at the University of Arizona it was the first time she felt deeply challenged with mathematics.

When she moved on to get a second master’s at the University of Arizona it was the first time she felt deeply challenged with mathematics.

“I realize now about the power of intimidation and lack of confidence,” she said. “I felt really intimidated right away because the other students had gone to prestigious schools, they’d had courses that I hadn’t, and I just immediately felt dumb.”

Eventually, Soto had to leave the program because she didn’t pass one of the exams.

“It took me a long time to finally say that out loud,” she said. “And now I say it because I know I’m not the only one that this happened to, and yet here I am. I think students need to hear that story. My biggest lessons have really come from failure.”

Teaching lessons around failure is one of the key aspects of Soto’s mentorship today.

“I came into her office for advice about teaching,” said Jocelyn Rios, a postdoctoral fellow in the mathematics department. “I was feeling discouraged about making mistakes in the classroom … Tensia told me that the most important thing to embody as a teacher is to be kind and generous. This advice really spoke to me and what I care about. It also speaks to the values that Tensia embodies as a teacher, mentor and human being.”

Following the advice and lead of her dad, Soto did not give up. She pursued her Ph.D. at the University of Northern Colorado, where her confidence in mathematics was restored. With spirits high, she took her first tenure track job at the University of Southern Colorado, now Colorado State University Pueblo. After nine years she returned to the University of Northern Colorado, began her research career, and after 15 years, proudly became a CSU Ram.

Teaching and mentoring with embodied cognition

After so much support from teachers and mentors throughout her life, Soto has dedicated her career and her research to holistically supporting students and her colleagues.

“In the short time that I have known her, I have grown tremendously, both professionally and personally, from her friendship and continued guidance and support,” said Arnold. “I know that Tensia will always be in my corner, rooting me on to achieve my dreams.”

Soto’s research focuses on creating classroom and research environments where students can express mathematical concepts through their bodies, a concept known as embodied cognition.

“I pay attention to how students convey their ideas through gesture, through body movement,” she explained. “The field really developed from linguistics. Babies’ first form of communication is through the body.”

Soto’s research focuses on how to help students experience mathematical concepts and convey them in their own, physical language. Soto can interpret student gestures to understand their mathematical thought process, even though they may not have yet internalized the proper, technical jargon. She also uses her own body and gestures as a form of communicating mathematical concepts to her students.

In a recent research study in collaboration with Jessi Lajos, a postdoctoral fellow in the mathematics department, they found that Soto’s “use of body-based activities and materials in the classroom positioned students who may not have the words to express their mathematical theories as central rather than peripheral participants,” Lajos said. “Her students formed a community that laughed together, shared excitement with one another and worked collectively to solve problems. Her work amplifies students’ voices and ideas in the classroom and facilitates peer support systems for students that extend beyond the classroom.”

Embodied cognition creates a more inclusive classroom, where all students regardless of mathematical language can participate in and create knowledge.

“Tensia shapes mathematics through her beliefs about who can do mathematics, her collaborations with others and the actions she takes,” said Arnold. “By inviting and encouraging all to pursue a major and career in mathematics, she is expanding the message that mathematics is for everyone. She is purposeful in her actions as a teacher, speaker and mentor; Tensia creates a space that welcomes each and every person.”