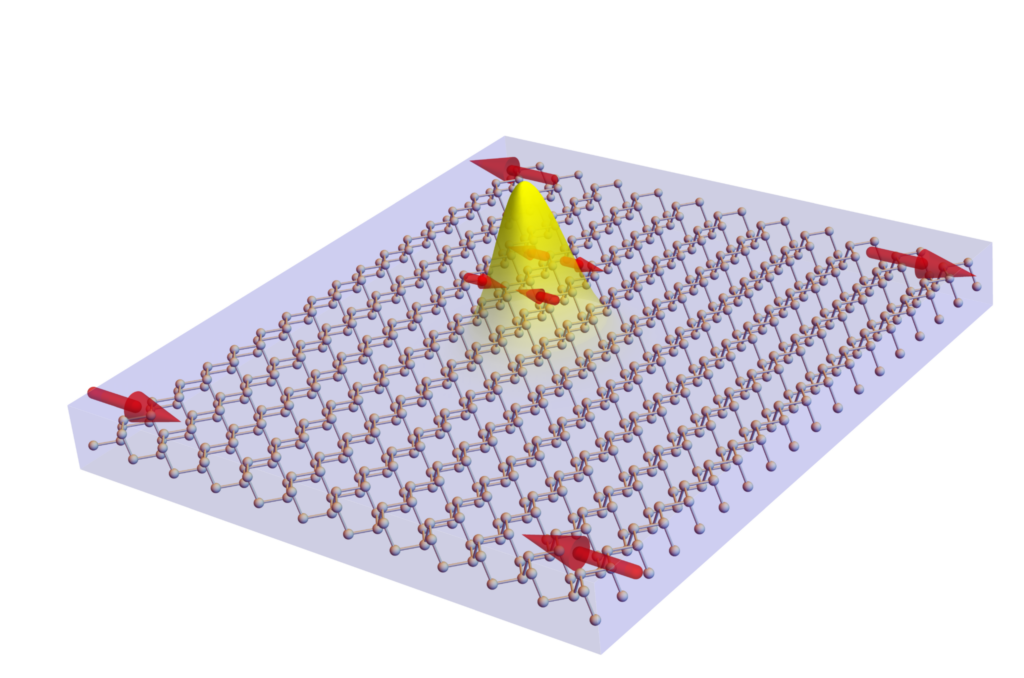

A wave packet carrying magnetic octupole moments and the corresponding corner spin pattern in monolayer phosphorene.

In modern technology, most data is encoded through electronic charges collected on tiny plates called capacitors. Depending on how many electrons they contain, they’re either assigned a one or a zero, creating binary code that can be used to represent a variety of information.

The catch? Capacitors must be charged multiple times a second, or else all the data is lost. This requires a lot of energy, which is why a laptop gets hot to the touch when multiple programs are open at once. Now imagine what’s involved in charging a supercomputer as it works to parse through a seemingly insurmountable collection of data.

What’s known as spintronics offers another solution, and Hua Chen, an associate professor of physics at Colorado State University, co-authored a paper with then-CSU postdoctoral scholar Muhammad Tahir in the journal Physical Review Letters that Chen says “plays a role in initiating a new direction” of this already cutting-edge field.

“We call it multipoletronics, and it uses what’s known as multiple moments instead of spin for both carrying and processing information – giving it similar benefits and impacts of spintronics, but more possibilities,” he said.

What is spintronics?

As computing capacity has grown, the actual devices doing the work have gotten smaller. It presents a perplexing problem in continuing to use charged electrons to carry data.

“Electronics are the bedrock of modern computer chips, but they have a fundamental limitation: The process produces so much heat, especially if you want to pack a lot of devices into a small area,” Chen said.

This is why scientists have looked at the spin of electrons to carry data instead. This involves much less energy, meaning there isn’t as much need to dissipate heat, even as devices get increasingly smaller.

Electrons either spin up or down, and magnets can be used to manipulate their direction, ultimately allowing devices to encode data without using nearly as much charge.

“However, this technology has had trouble because these devices are susceptible to external magnetic fields, which are not so easy to shield,” Chen said.

That’s why scientists like Chen are looking beyond simply spin.

New possibilities with ‘multipoletronics’

Chen’s latest research explores how some materials can make electrons spin from multiple poles – offering more possibilities beyond simple combinations of up and down. These materials are different from traditional magnet materials, meaning they’re less susceptible to external fields.

“This research is basically a step forward compared to the idea of spintronics, where spin is like an arrow that points in one direction and is attached to each individual electron,” Chen said. “The question is whether spin is the most effective object for practical applications. That’s where the idea of multipole movements – or the shape of the spin – comes into play.”

However, these shapes are hard for scientists to quantify and predict. Chen’s research allowed him to isolate some multipole moments that occur when an electric current flows through phosphorene and build a formula to show how they moved.

“Using multipole moments instead of spin for carrying and processing information allows for greater amounts of data to be shared at an even lower level of energy than spintronics,” Chen said. “In the future, this information could allow for big developments in terms of processing speed.”