Researchers at Colorado State University are making advances in understanding the links between socioeconomic status, sleep and brain development in children.

Their approach combines MRI scans of brain structure and function with family surveys on aspects like household income and economic hardship, which can often influence children’s sleep patterns.

The work – recently published in Brain and Behavior – is led by Assistant Professor Emily Merz in the Department of Psychology. She said it may be key to forming a better understanding of the effects of adversity on early brain development and how early interventions can support children.

While many children do not get the recommended amount of sleep, those from disadvantaged families are especially at risk of low sleep quantity and quality. Merz said that may be due to increased unpredictability in their lives such as changes in household composition, periods of parental unemployment or housing instability. It could also be due to lower quality sleeping environments such as noisy sleeping areas.

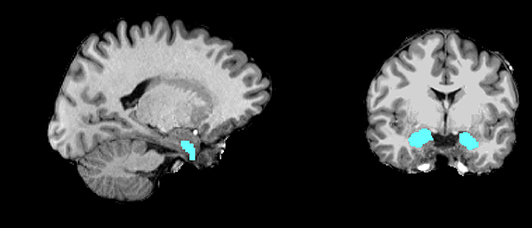

To test those relationships, Merz and her team surveyed 5- to 9-year-old children from a variety of backgrounds, demographics and family situations. Together, 30% of the children in the sample came from families with incomes that fell below the U.S. poverty line. The group also included parental education levels ranging from six to 20 years – offering a solid cross-section of home experiences. They then carefully measured brain structure of the children using MRI scans to study the size of the amygdala and cortical thickness.

Merz said the results showed that lower family income and parental education were significantly associated with shorter weekday sleep duration in children.

“Shorter sleep duration was significantly associated with reduced cortical thickness in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions and smaller volume of the amygdala – a brain region key to emotion processing,” Merz said. “We also found that consistency in family routines significantly mediated those associations. This might imply that socioeconomic disadvantage interferes with the consistency of family routines – potentially increasing children’s stress and reducing their sleep time, which then impacts brain development.”

Cognitive neuroscience graduate student Melissa Hansen was the lead author of the paper and recently presented additional findings from the research at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s annual conference. Merz said Hansen and the rest of the team will now continue the work using fMRI — functional magnetic resonance imaging — scans to analyze functional connectivity between brain regions in relation to sleep duration.

“Our newest findings suggest that sleep insufficiency may be associated with not only the brain’s size and structure but also the function of emotion processing brain circuits in children,” Merz said. “This may possibly explain why reduced sleep leads to greater susceptibility to negative emotions. Although most developmental studies of sleep have focused on teens, this research underscores the need to assess and support children’s sleep health prior to adolescence.”

Merz added that this research could inform policy and programs that support getting children consistent sleep during this key age.

“Childhood is a sensitive period in development when environmental experiences can have powerful and lasting influences on the brain,” she said. “Our work – and work done by other labs – suggests that antipoverty policies that support families have the potential to change the trajectory of children’s lives.”