Last fall Colorado State University’s Department of Biology hosted a brand-new course: Recognizing and Addressing Oppression in the Sciences.

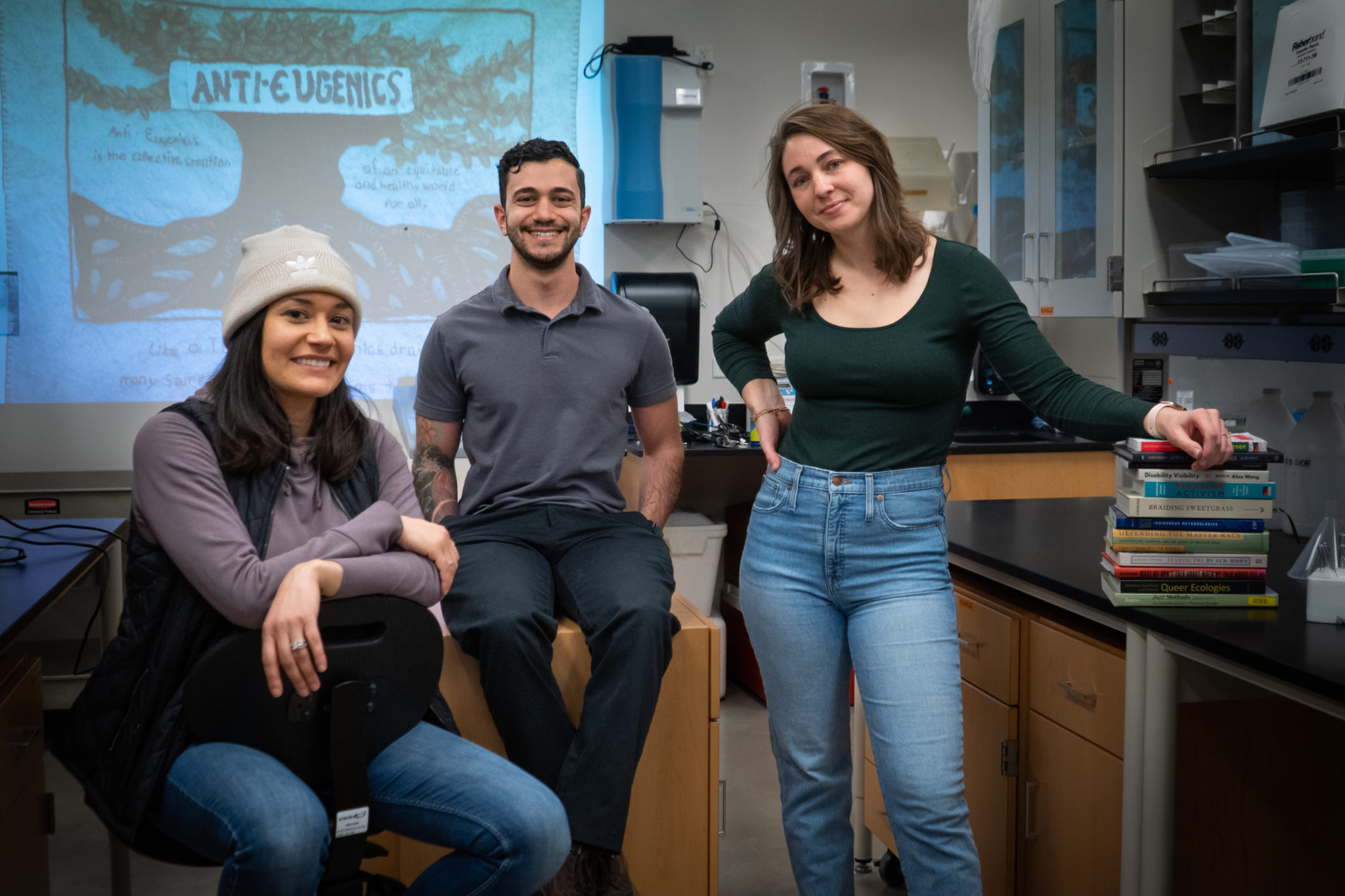

Biology graduate students Beth Wittmann, Amir Alayoubi and Marina Rodriguez co-developed and facilitated the course in the hopes of creating a learning environment unlike any other.

Wittmann, whose Ph.D. research delves into the often-overlooked, oppressive history of science, had considered teaching a course for some time.

“What we covered in class are like the roots that hide underground, and what we usually look at is what’s on top, what’s presently happening,” said Wittmann. “Taking the approach of ‘why?’ and digging deeper and deeper has been helpful for me, personally, looking at these topics.”

Alayoubi and Rodriguez, both deeply passionate about diversity, equity and inclusion, wanted to do something actionable that went beyond the standard discussion of recruitment and retention in STEM.

“We were all so tired of hearing about the leaky pipeline and all the statistics that go into it,” said Rodriguez. “That’s the problem, but where does that problem stem from?”

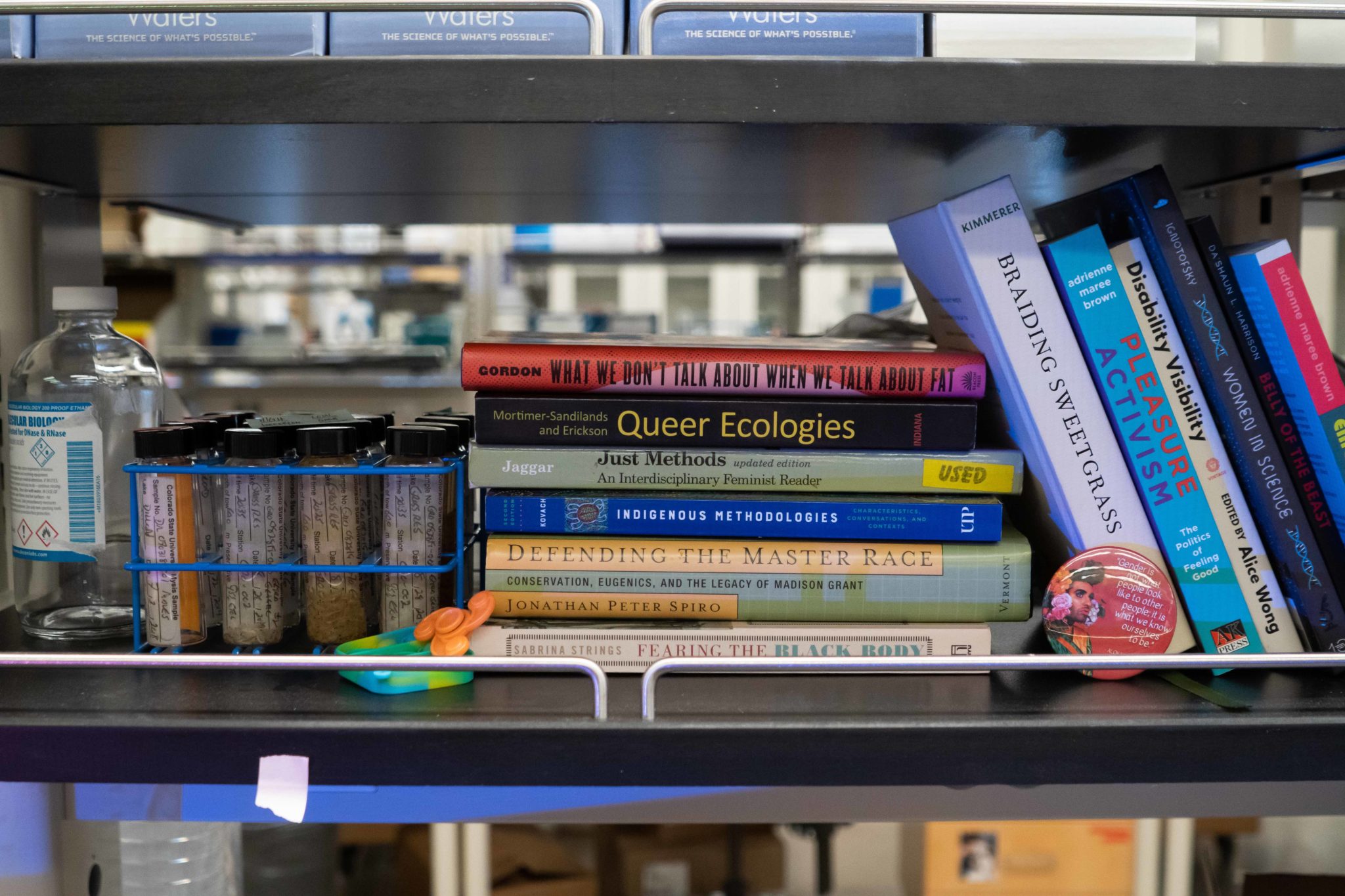

The union of the three catalyzed the creation of a course that didn’t shy from big topics: the history of eugenics and forced sterilization, the myth of overpopulation, anti-fat bias, and the connections between science and colonialism, to name a few.

“The fingerprints of scientists from the past are all over the science that we study today,” said Wittmann. “It really matters to know who they were, what they did and where we come from. We want to learn our whole story as scientists.”

Finding their passions for DEI

Alayoubi, Wittmann and Rodriguez discovered their independent passions for diversity, equity and inclusion work through their life experiences, despite each coming from different backgrounds.

Alayoubi was born to Syrian immigrants and raised in a low-income suburb of Los Angeles. He was forced to grow up quickly, helping his mom translate bills and navigate divorce, working to help his family and experiencing Middle Eastern stigma and racism in the wake of Sept. 11.

Alayoubi was a part of the 50% of his high school class that graduated and attended California State University San Marcos for his undergraduate degree. He found his passion for neuroscience after his father experienced an ischemic stroke during surgery and permanently lost blood flow to most of the right side of his brain.

To attend school and continue pursuing research, Alayoubi worked 70 hours a week, sold his car, and rented out his apartment’s rooms to pay for school and volunteer in a neuroscience lab.

Now a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biology, Alayoubi thinks about the other students like him who couldn’t afford higher education and hopes to eventually change things for them.

“There are so many people who couldn’t have done this, who would make amazing scientists,” he said.

Rodriguez is part of a Hispanic family from San Antonio and is the first in her family to go to college.

Determined to study in Colorado, she “threw all (her) eggs in the CSU basket” and moved to Fort Collins for her undergraduate degree, she said. After her freshman year, she was forced to drop out because she couldn’t afford tuition.

After saving up money, she returned to finish her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at CSU.

“I worked so hard, I was tired all the time,” she said. “I was working multiple jobs at a time and still getting good grades and valuing my education. But I had to work three times as hard as anyone else just to be level with them.”

Now a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biology, Rodriguez’s mission is like Alayoubi’s.

“I eventually made it through all that and realized no one should have to do this to go to college. It should not be this hard,” she said. “That motivated me to help other people, especially people with marginalized backgrounds.”

Wittmann is from a white, upper-middle class family from Scranton, Pennsylvania, and attended the University of Vermont for wildlife biology.

She moved to Colorado to pursue her interest in herpetology and worked many seasonal jobs, making ends meet in the off seasons via parental help or applying for unemployment.“As a woman in the field, I always felt like I was showing up to a party that no one wanted me at,” she said. “I always had to hike twice as far or carry twice as much, and I started collecting stories from other women about the harassment they’d experienced in the field.”

After a near-two-year stint of unemployment, Wittmann’s experiences in the field came to a head.

“It was a really terrible time but looking back on it was a huge period of growth for me,” she said. “A big part of that growth was learning what it means to be a white person in the United States.”

After applying what she had learned about social justice with the Amplify Learning Community, a first-year community focused on holistic DEIJ practices and inclusion in STEM, Wittmann is now a Ph.D. student in biology with a specific research focus on diversity, equity and inclusion in natural resources.

A new kind of course

When Wittmann, Alayoubi and Rodriguez joined forces to create the course, they were intentional about their goals from the outset. They wanted to make the class as inclusive as possible by providing fidget toys and food, offering breaks and regularly changing the physical layout of the furniture in the classroom.

When Wittmann, Alayoubi and Rodriguez joined forces to create the course, they were intentional about their goals from the outset. They wanted to make the class as inclusive as possible by providing fidget toys and food, offering breaks and regularly changing the physical layout of the furniture in the classroom.

Instead, the class periods would be lecture- and discussion-based, focus strongly on building community and finding humor even during heavy topics. All three instructors counted on shared learning and planned to partially rely on the existing knowledge base of the students to expand the class to its full potential.

After sending the syllabus out for rounds of editing from peers and faculty and meeting weekly over the summer, the moment came for students to register.

“It felt like putting out a bat signal into the depths of STEM and seeing who pinged us back,” Wittmann said.

Once the semester began, the course challenged and welcomed students from all areas of STEM and from all backgrounds.

From discussing queer ecology and Indigenous epistemologies, listening to guest speakers, drawing and free writing, to examining the ways modern academic spaces uphold principles of whiteness, the course delved into the overlaps between science and oppression in ways many students had never experienced before.

“Sometimes it was tough to sit there and realize what you thought previously was wrong,” said Carina Donne, a second-year Ph.D. student in the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology. “But that’s a good thing even if it’s uncomfortable – it’s growing pains.”

Many students questioned and expanded their world views.

“I often was compelled to reassess my conceptions of the world and decide if they were my own that I could stand by, or ones that were handed down to me,” said Andrew Paton, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Biology.

The three co-facilitators shared the burden of teaching between them, allowing for those who just taught emotionally difficult modules to rest, while the next person stepped up to the plate.

Relying on guest speakers and the individual knowledge of the students “showed us an even more vast world than each one of us could probably peek into by ourselves,” said Witmann.

Wittmann, Rodriguez and Alayoubi have high hopes for the future of the course, understanding its potential impact and looking for sustainable ways to carry it forward.

“We’re dealing with a room full of future scientists,” said Alayoubi. “People are going to have their own labs, be directors of programs, teachers, industry scientists. Even if they take one thing away from this class, the ripple effects could be huge.”