Like every great scientist, Greg Florant, professor emeritus in the Colorado State University Department of Biology, got to where he is today through experimentation, exploration, curiosity and creativity.

Florant discovered he had a knack for science at a young age. His path towards becoming the award-winning scientist he is today was paved with creative problem solving and an innate curiosity about the natural world. The story of his journey to scientific excellence is as follows:

Part 1: Reading

Florant initially found his love for biology through his dislike of reading.

“My mom would take me to the library, and the librarian said, ‘Why don’t you get your son to read stuff that he really likes? That will improve his love of reading,’” said Florant. “So, my mother turned to me and asked, ‘What do you like to read?’”

What piqued Florant’s interest? Birds.

Reading about falconry and birds of prey not only increased his interest in reading, but his interests in biology and science as well.

Florant’s love for math and science flourished in high school. He ranked high among his peers, earned high marks in Advanced Placement chemistry and math, and began to look for universities with robust ornithology programs.

Part 2: Falcon eggs

As a senior high school, Florant began working in a research lab at the University of California, Berkeley, studying the causes of thinning eggshells in peregrine falcons. He ran a gas chromatograph to analyze the effects of chemicals like dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on falcon eggs.

One day, Florant had a question about PCBs and visited the Berkeley library, where he thoroughly stumped the librarian. She pointed him in the direction of a visiting chemistry professor from Cornell University.

“I walked over to him, a 19-year-old with a big ‘Afro, and I said, ‘Hey, my name is Greg Florant I’m interested in this conversion of polychlorinated biphenyls, do you know anything about that?’” he said.

After an hour discussing conversions, the professor urged him to apply to Cornell.

Florant went on to become one of the first Black students to earn a bachelor’s degree in biology from Cornell University in 1973.

Part 3: Ravens

Florant won a Ford Foundation Scholarship to attend graduate school and went on to become the first Black student to graduate with a Ph.D. in biology and physiology from Stanford University.

He spent his first year as a Ph.D. student studying raven’s unique adaption to extreme climates, focusing specifically on the function of their black plumage. He raised several ravens, keeping them in an aviary atop a Stanford building and training them to be comfortable and responsive in his presence.

Florant’s plans for his thesis were foiled, however, when someone set all his ravens free.

“I was heartbroken,” said Florant. Devastated, he had to change plans, and fast.

His graduate adviser suggested studying marmots. Not a marmot enthusiast, Florant reluctantly agreed.

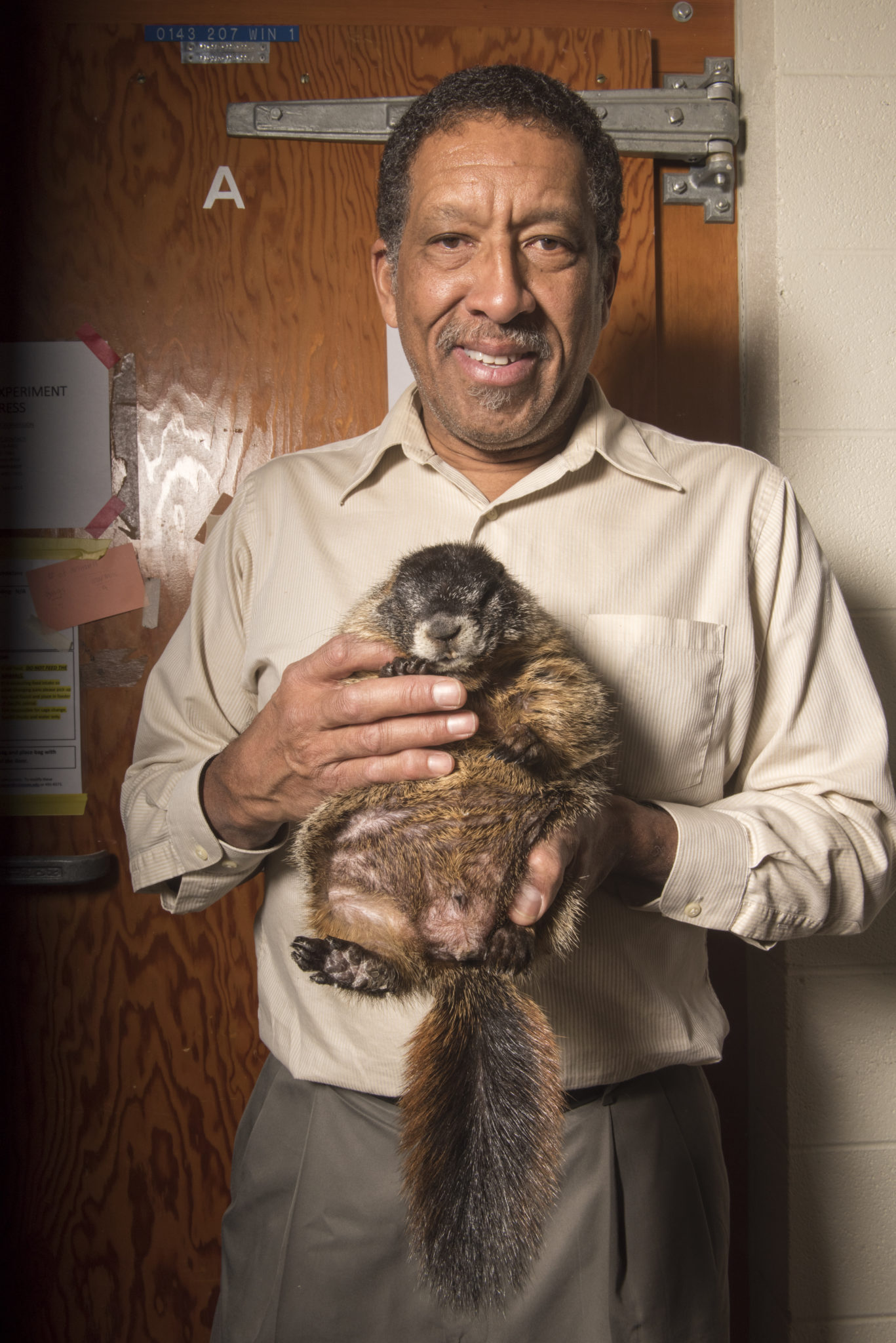

He’s been passionately studying hibernation physiology in marmots ever since.

Awards and achievements

Greg Florant has been widely recognized for his contributions to the scientific field.

He was recently named a Fellow of the American Physiological Society, one of many awards he’s garnered over his long career in biology.

“This Fellowship couldn’t have gone to a more qualified and passionate recipient,” said Jan Nerger, dean of the College of Natural Sciences. “Greg is a researcher of the highest caliber, a dedicated teacher, and a committed advocate for students from all backgrounds. I am thrilled that he has once again been recognized for his outstanding character and hard work. Congratulations!”

He was also elected as a Fellow to the AAAS in 1988, is the recipient of three Fulbright Fellowships, and has served on two prestigious boards in the scientific community: The National Science Foundation Bio Advisory Board, which reports to the NSF director, and the NIH NIDDK study section B which evaluates important NIH training programs.

Part 4: Bacon grease

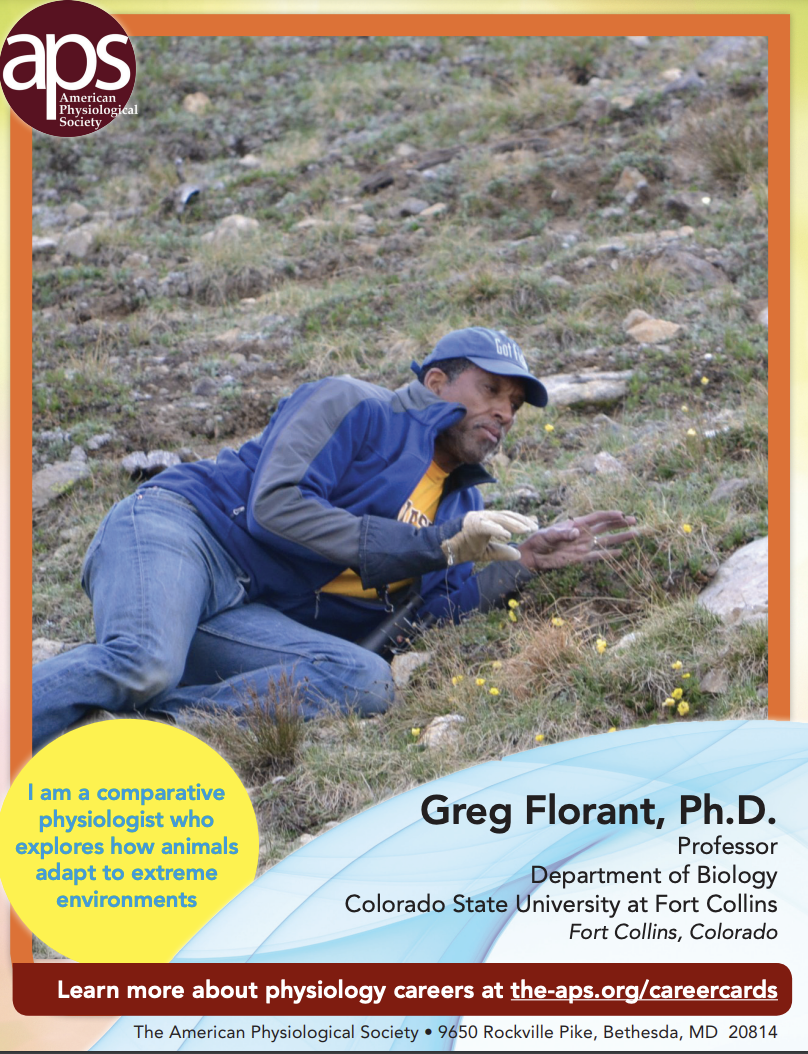

Florant spent much of his research career focused on marmots and the physiological mechanisms they use to adapt to extreme environments.

When he began this research, however, marmots proved notoriously difficult to trap. No one in the scientific community had identified an effective way to attract marmots.

After many unsuccessful trips into the alpine, Florant considered the type of food he’d prefer to eat after a long, fat-depleting hibernation: greasy fast food.

With a jar of bacon grease secured from a local diner, he traipsed back up into the mountains. He returned to Stanford with more than 30 marmots the following day.

“I had everything from crows, to marmots, to small children going in that trap to get the grease,” joked Florant.

To this day, high-fat foods have become the international standard for baiting marmots.

Florant’s findings on hibernation and weight gain in mammals have become a crucial part of our understanding of human obesity and weight regulation.

“His work helped establish the basis for defining the physiology of hibernation and ultimately led to some of the seminal work on the hormonal regulation of metabolism during hibernation, which served as the basis for much of the current work on the endocrinology of hibernation and prolonged fasting,” wrote Rudy Ortiz, a professor of Physiology & Endocrinology at the University of California, Merced, in his letter recommending Florant to be named an American Physiological Society Fellow.

Part 5: A legacy

Over the course of his career, Florant has been widely recognized as an excellent scientist, teacher and mentor.

His successes, however, have not come without difficulty. Forging the path for future generations is not light work, and through each stage of Florant’s academic career he navigated being one of very few people of color in many primarily white spaces.

“I had a dual life,” said Florant. “I did a lot with my biology friends, but I was also a member of the Black Student Union at Stanford, and I had a lot of Black friends. I lived in two worlds.”

At CSU, Florant often taught students who had never had a Black professor before.

“I’d tell them, this could be interesting,” he said. “Maybe you’ll learn something besides just biology.”

Florant’s time at CSU was spent not only on teaching and research, but on advancing critical programs to increase diversity, equity and inclusion at the University and beyond.

He brought over $1 million to CSU for the Native American Women in Science Scholarship, was involved with the Alliance for Graduate Education and the Professoriate program and co-directed the Bridge to Doctorate program. He also helped start the Graduate Center for Diversity and Access program which has a 90% graduation rate and directed the Graduate Center for Inclusive Mentoring.

Long devoted to sharing the importance of science and high-quality research, as well as the power of excellent mentoring and inclusivity, Florant hopes his legacy is one that moves the needle forward.

“I hope that I’ve left the institution in a better position, as a better place than when I first came here,” he said. “I’m hoping that I influenced the number of students and faculty members to carry on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion work. I’m hoping that I set an example and high bar for people to continue to be good mentors, good researchers and good teachers, to all people and to all students.”