Understanding the role of a tiny protein in the brain could be the key to understanding the development of dementia associated with neuro-degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s.

James Bamburg and Laurie Minamide, researchers in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Colorado State University, have been studying the protein in question, cofilin, for over 30 years.

Bamburg discovered the first member of the cofilin protein family, and he and his research team have since found that cofilin is vitally important to the formation of synaptic connections in the brain, and disruption of its normal function may result in the loss of memory development and learning functions.

Now, they are hoping to use this new knowledge to develop drugs that target cofilin disruption for use in clinical trials to prevent or rehabilitate memory loss in patients with dementia.

How it works

To understand the connection between cofilin and dementia, it’s important to understand the role cofilin plays in creating the brain’s internal communications network.

Process 1: Synaptic connections

Nerve cells, called neurons, form connections, or synapses, that act as the site of transmission for electrical nerve impulses. Neurons start out as round cells (neuroblasts) that form long thin extensions or dendrites that receive input from hundreds of thousands of other neurons, and axons, which transmit signals over long distances to other neurons.

Synapses are essential for connecting sensory organs, and for the formation of memories. Thus, anything that would inhibit the formation of synapses could inhibit memory formation, leading to diseases such as Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Cofilin is key to the function of axons, dendrites and synapse connections. The researchers think interference in cofilin activity can lead to the blocking of synapse formation, which is linked to neurological disease processes.

Process 2: Cellular mobility

The ability of cells to move and carry out organized cellular activity is dictated by the organization of the cytoskeleton, globular protein subunits that assemble into long polymers called filaments. Actin, one of the most abundant of these cytoskeletal proteins, undergoes assembly into filaments that are used in many cellular processes, such as pushing the membrane forward during cell migration.

The cofilin protein binds near one end of an actin filament, severing it into pieces, which then reassemble at the opposite end of the filament, like a treadmill propelling the cell along.

Meet the researchers

Bamburg and Minamide have been married and working together for many years.

“We did have to establish a rule very early in our marriage that Jim’s not allowed to talk science to me before 7 a.m.,” laughed Minamide.

“I thought it was 6:30!” retorted Bamburg.

The two laughed about Bamburg’s early-morning science epiphanies, reminisced about years of research together, making new discoveries, and sneaking into each other’s workspaces during sabbaticals when partners were not allowed to work in the same lab.

“I don’t know what I would do without Laurie, both in terms of lab work and just in life in general,” said Bamburg. “She’s been my best friend and certainly is the person that everyone in our lab relies on for core knowledge about everything.”

“Jim is my best friend too,” said Laurie. “And he makes my lunch every day!”

Process 3: Wiring the nervous system

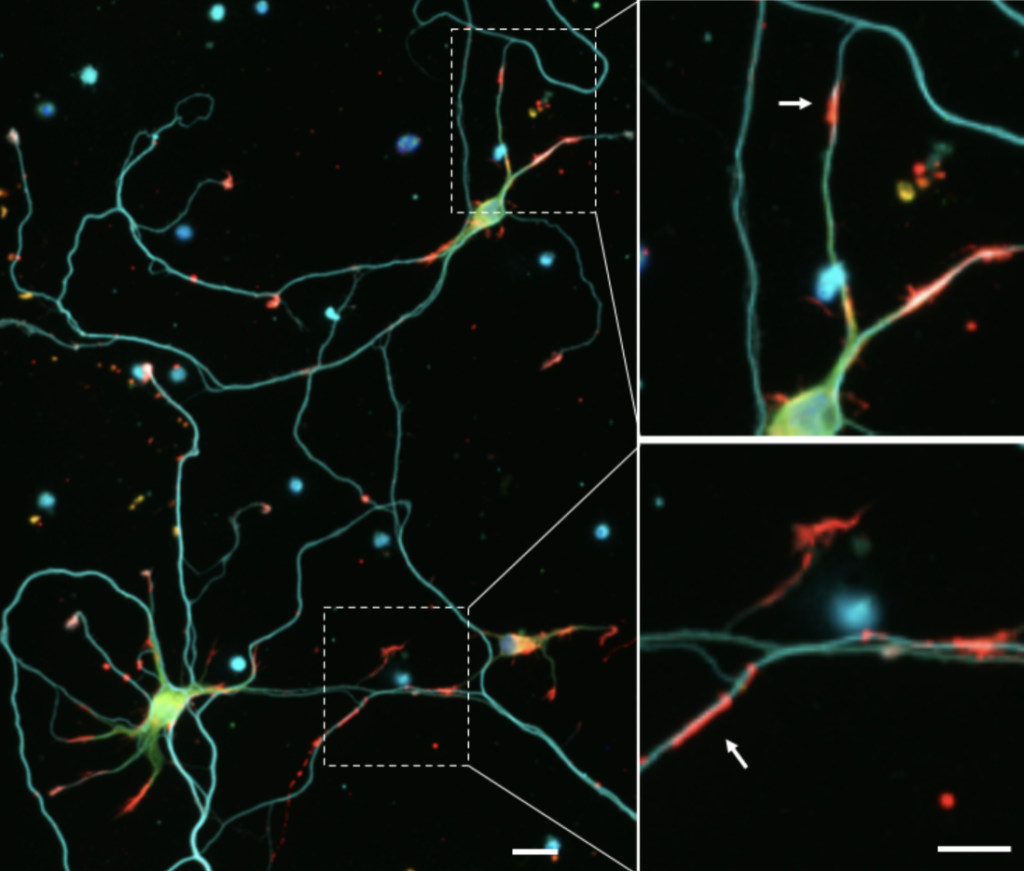

Cofilin uses the same processes of cellular migration to start the process of extending axons and dendrites (collectively called neurites) off of neuroblasts toward other cells, eventually creating synaptic connections.

This protrusion of neurites causes the formation of a hand-shaped growth cone that migrates away from the cell body.

The actin filaments, aided by cofilin, that help reassemble the cytoskeleton at the leading side of the cell grow and branch “like 10,000 little fingers pushing that membrane forward,” explained Bamburg.

For the growth cone to find its target and form proper synaptic connections within the nervous system, it must be able to respond to signals steering it toward the attractant. An attraction factor released by the target cell modulates the activity of cofilin across the growth cone to selectively alter the position of actin disassembly and reassembly.

When growth cones reach their target, a synapse begins to form, creating connections with other neurons within the brain to create the circuitry for learning and formation of memories.

Thus, anything that inhibits the formation of synapses could inhibit memory development. If cofilin function is limited in some way, would that prevent synapse formation and thus lead to the development of degenerative disease?

Process 4: Nuclear rods

Minamide discovered that in cultured neurons under stress, elongated rod-shaped bundles of cofilin-saturated actin filaments formed within axons and dendrites. These rods both sequester cofilin, removing it from its usual function within the cell, and can grow to completely block transport within the neurite, leading to its atrophy.

Bamburg and Minamide’s research has shown that these rods occur almost exclusively in brain sections affected by Alzheimer’s, strongly suggesting that the sequestering of cofilin into rods might be a major pathology responsible for synaptic dysfunction and dementia.

“We think this is what happens in lots of types of dementia in the hippocampus, the area of the brain associated with short-term memory development,” said Bamburg. “These rods cause the loss of synaptic connections that are necessary for memory and learning.”

During the past 10 years, investigators within the Bamburg lab working with national and international collaborators have identified cofilin-actin rod pathologies in many rodent models of neurodegenerative diseases in which dementia is an outcome, such as

Parkinson’s disease with Lewy body dementia, AIDS dementia, neuroinflammation, and stroke.

Taking it to clinical trial

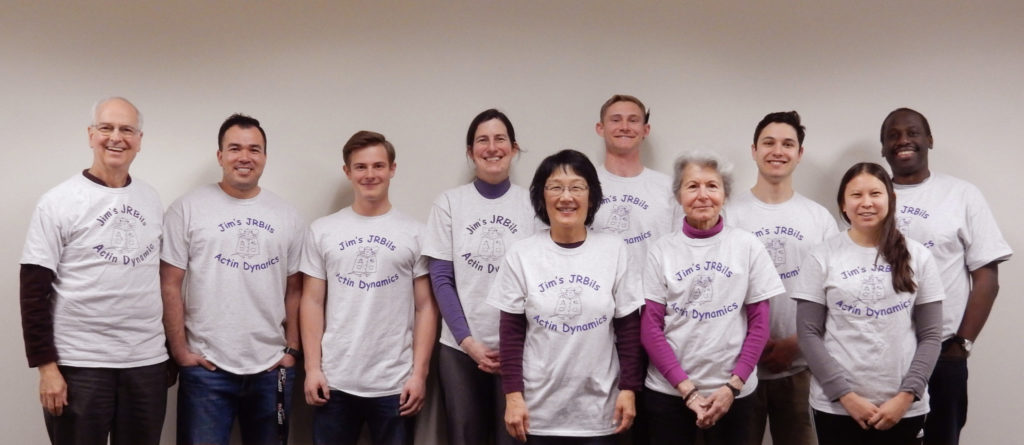

With their longtime CSU research colleagues Barbara Bernstein, Alisa Shaw and O’Neil Wiggan along with several postdoctoral researchers, and Ph.D. and master’s students, the Bamburg lab has been studying cofilin and its role in development and function of nerve cells since Bamburg discovered the first member of the cofilin.

Now, the lab has turned its focus to preventing rods by inhibiting the single family of receptors that lead to rod formation.

The reagents they are currently testing are small peptides designed originally to prevent HIV infection, but when added to neuronal culture with rod-inducing agents, prevent rod formation.

They’re joined in this quest by Tom Kuhn, an adjunct professor at CSU, and by former Ph.D. student Lubna Tahtamouni, as well as graduate and undergraduate students.

“Whether or not the peptides will help neurons restore their communicative ability, we don’t know,” said Bamburg. “But the goal of this project is to determine whether these drugs will protect synapses, and if so, try to get these drugs into a clinical trial where it can be shown that they might prevent further cognitive decline and, hopefully, reverse the loss of cognitive function.”

Bamburg says he feels he owes a debt to the taxpayers who have supported this research for so long, and notes how important foundational science is to medical advancement. “Maybe [our research] didn’t help anybody health-wise until we got to the point where we really understood much more about these proteins and how they behave, and now its reaping some benefits.”

Researchers must hyper-focus the small things, like one tiny protein, to unlock the secrets behind world-changing discoveries.