Power of Light

CSU chemist seeks to build a better way to make COVID-19 drug, using light by Katie Courage published Sept. 11, 2020As the novel coronavirus continues to sicken tens of thousands of people a day in the United States, scientists have found that the antiviral medication remdesivir can help some patients recover from severe COVID-19 more quickly.

But remdesivir has been in short supply around the world. This is in part because it is very difficult to make, involving numerous steps that require dangerous chemicals and harsh manufacturing conditions. It also takes a long time to synthesize – and, using current methods, doesn’t create very much product.

This is where Colorado State University Associate Professor Garret Miyake and his colleagues are hoping to step in. Miyake’s lab explores novel ways to make new molecules using the power of light. It might sound fantastical, but it is real, cutting-edge chemistry.

“Our lab is focused on harnessing light energy for driving chemical transformations,” said Miyake, who heads a lab in the Department of Chemistry in the College of Natural Sciences. “We are working on developing new ways to build molecules. We recognized that our expertise could be applied to improve some of the key steps in the synthesis of remdesivir.”

They hope to use their light-driven process to devise a faster, cheaper, and safer way to make this important antiviral medication. A spinoff company Miyake helped to start through the university’s technology transfer arm CSU Ventures, called New Iridium, recently received a $256,000 grant from the National Science Foundation’s Small Business Technology Transfer funding group. From that grant, Miyake’s CSU lab will receive $85,000 to further pursue this promising research.

“I am excited to apply our team’s expertise in chemistry toward addressing an urgent global challenge,” Miyake said, who also received his Ph.D. from CSU. “Most of the time we work on very fundamental problems, but here, we are trying to save people’s lives.”

Radical chemistry

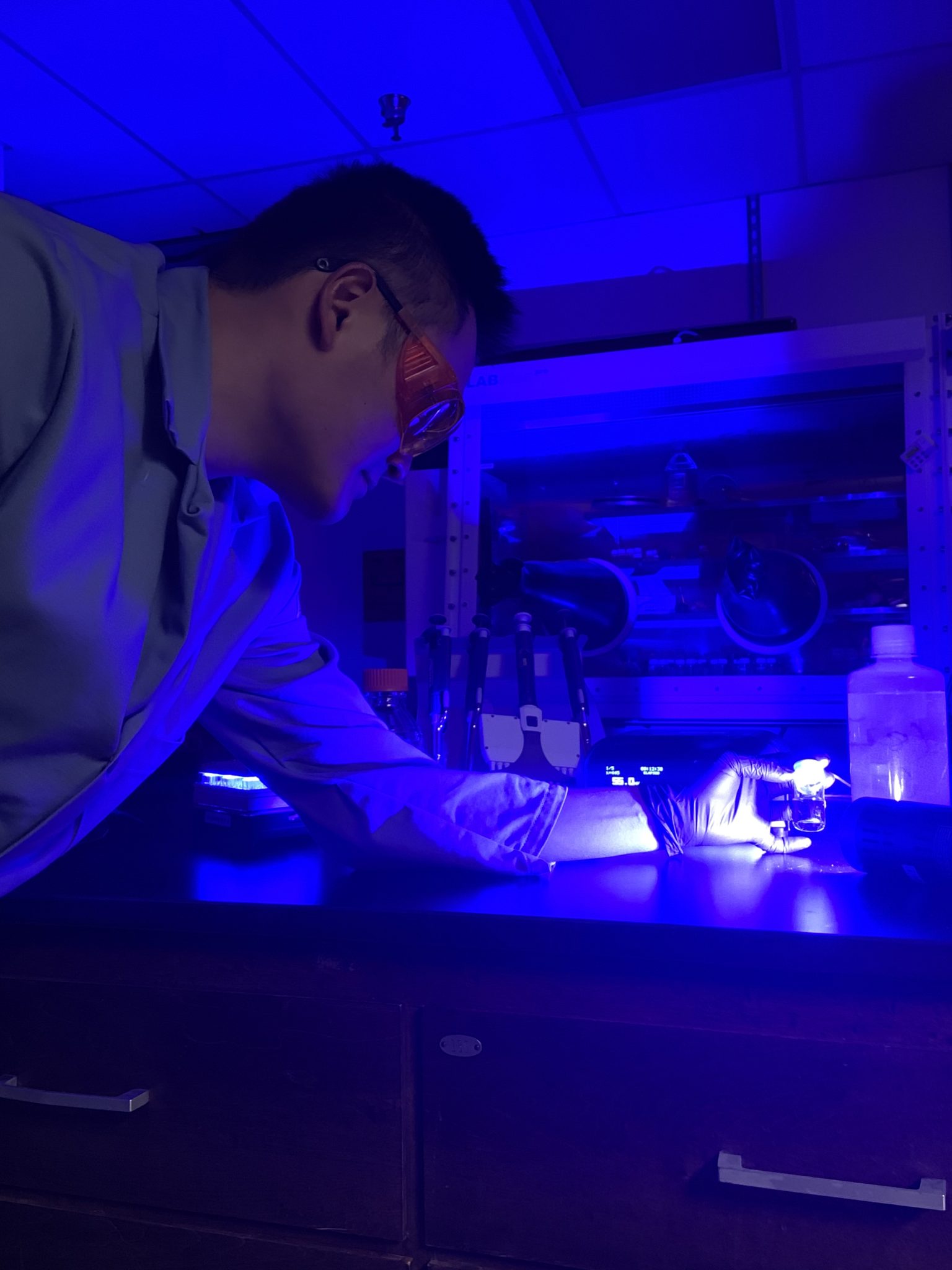

Chern-Hooi Lim, New Iridium CEO, checks the reaction mixture at the Miyake Lab at CSU, which is leased by New Iridium.

As Miyake and his colleagues at New Iridium saw the promise of remdesivir, and the ravages of COVID-19, they knew their research and patent-pending technology might be able to help.

Much of chemistry – and chemistry-based manufacturing – relies on heat to jumpstart chemical reactions. “Chemical catalysis is arguably the most important contribution that chemistry has made to society,” Miyake said. We have this process to thank for countless things we use every day, from plastics to household cleaners to common medicines.

At the molecular level, this heat breaks and reshapes chemical bonds physically. Practically speaking, this sort of chemical manipulation can take expensive equipment and create potentially hazardous work environments.

But Miyake’s work, which is part of an entirely new branch of the field called radical chemistry, leverages light to do this work. Instead of knocking apart molecular bonds with the vibrations from high temperatures, their so-called photoredox catalysis “captures energy from visible light and transfers that energy into the reaction mixture,” explained Chern-Hooi Lim, CEO and founder of New Iridium. “Using light, the molecules are not shaken, but rather the electrons change position, which induces the molecular transformation.”

Which means that reactions can take place in much less harsh conditions, and often even at room temperature.

“It’s a much more powerful tool than heat-driven approaches,” Lim said. He compares it to the technological leaps from land lines to cell phones or film to digital photography. “The new technologies can do tricks that are beyond the reach of traditional methods.”

Making medicines – so more people can use them

Synthesis of an organic photocatalyst.

Although Miyake’s work typically stays within foundational science, the application of his photocatalysis research to make medicines holds promise for very real life-saving interventions.

For example, the photoredox catalysts can provide essential components to drug manufacturers much more quickly and cheaply than traditional chemistry can. This means pharmaceutical manufacturers, which can spend a decade and billions of dollars before they bring a new drug to market, could afford to test more compounds faster – and more cheaply. And once a successful drug compound is found, manufacturing it could also be scaled up faster and more affordably.

“We can streamline the existing process by improving steps that are major bottlenecks in the production,” Miyake said.

For remdesivir, this means the drug maker could skip the difficult and expensive steps in traditional chemical manufacturing to create the same intermediate compound “that can then be easily processed the rest of the way to remdesivir,” Lim said. “This shortcut significantly reduces the complexity, duration, and factory requirements for the remaining production.”

This also has important implications for global access to medicines. A process like photoredox catalysis is easier for labs to implement than many of the involved steps currently needed to make remdesivir. Which means that more manufacturing locations could be spun up, even in resource-poor settings, Lim noted, which would help immensely as global demand for this drug surges.

New Iridium is currently in talks with Gilead, the maker of remdesivir, to explore scaling up the streamlined process.

The application of Miyake’s work doesn’t stop with this COVID-19 drug. Through New Iridium, he hopes to be able to use the new CSU-based research and discoveries to help in developing other drugs – and even in screening for future viral threats, he said.

Miyake began his work on these processes when he was on the faculty at the University of Colorado Boulder, where Lim was a post-doctoral researcher in his lab. The technology being used now is jointly owned by CSU and CU and is undergoing review for a patent. CSU is featured as a sub-awardee of the NSF grant to New Iridium.

“Collaborating with the Miyake lab allowed us to quickly scale the research beyond what we could do,” Lim said.